Meetings and Events

Spring 2013

Vol. 8, Issue 1

Winter 2013

Vol. 7, Issue 2

Spring 2012

Vol. 7, Issue 1

Spring 2011

Vol. 6, Issue 1

Fall 2011

Vol. 6, Issue 2

Spring 2010

Vol. 5, Issue 1

Fall 2010

Vol. 5, Issue 2

Spring 2009

Vol. 4, Issue 1

Fall 2009

Vol. 4, Issue 2

Spring 2008

Vol. 3, Issue 1

Fall 2008

Vol. 3, Issue 2

Fall 2007

Vol. 2, Issue 2

Winter 2007

Vol. 2, Issue 1

Summer 2006

Vol. 1, Issue 2

From Dust to Discovery

In a gigantic freezer in a warehouse about 30 miles from the NIH main campus, coral from the quiet depths of the South Pacific, leaves from a rare tree in southern China, and bacteria from a crustacean of the cold Atlantic waters sit frozen in time, waiting their turn to possibly treat, cure or even prevent two of the planet’s worst ailments: cancer and AIDS.

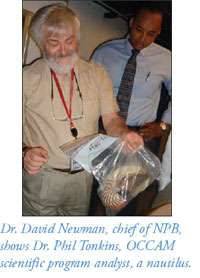

Thousands of plant, marine, and microorganism specimens collected from a myriad of places in the world are sent to the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Natural Products Branch (NPB) each year. “We are the hub of a hub-and-spoke operation,” says Dr. David Newman, chief of the NPB. Here, they are kept frozen until sent out and tested by NCI researchers - as well as other researchers around the world - looking for natural agents to fight cancer and AIDS.

Researchers looking for these new drugs have plenty of reasons to be sifting through nature. Traditional Chinese Medicine, which deals mostly with natural products, has been producing remedies for a variety of diseases for years, including the herbal remedy from the plant “sweet annie” (Artemisia annua),which has been used in China for almost 2,000 years. Its main, active constituent, artemisinin, has been found to be effective against fevers and resistant malaria. And today, over 75 percent of the world’s population uses some fashion of alternative, or traditional, medicine involving natural products, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports.

“There is no question that Traditional Chinese Medicine has its value,” Dr. Newman says. But there is a difference between the traditional usage of natural products and what NPB is looking for, Dr. Newman explains.

NCI breaks specimens down to an unrecognizable pile of dust, aiming to study the active components, whereas traditional practitioners use the original, intact specimen for remedies. “We’re interested in finding those active compounds within the organism, not necessarily the extract as a whole,” Dr. Newman states.

But cancer researchers studying complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) still learn from the discoveries stemming out of NPB.

“Knowing the basic components and mechanisms of action of a natural product benefits cancer CAM researchers,” says Dr. Jeffrey D. White, director of the Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine. “It’s the investigation of the natural agents’ activities – whether it’s the entire specimen or just one part of it – that helps researchers determine which cancer treatments are worth pursuing.”

Modern, FDA-approved drugs have their fair share of plant life in them, too - even if it’s not in their entirety. According to the WHO, about one-quarter of today’s drugs are derived from plants first used traditionally. Popular drugs that fight cancer like camptothecin and rapamycin were derived from a plant and fungus, respectively, and several drugs on the market are synthetic versions of certain agents in plants.

“So many things come from plants, even the indigo in blue jeans…,” comments Dr. Newman. “It’s things like these that lead to novel treatments of cancer.”

Take the bark of a tree, for example. Back in 1962, researchers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture recovered bark from a Pacific yew in the Pacific Northwest, which led to multiple tests by NCI and NCI contractors, including the Natural Products Laboratory in Research Triangle Institute, N.C., and subsequent clinical trials of the active compound. The result was a drug known as paclitaxel (Taxol®), which is used to treat breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, and is perhaps the biggest success for NCI-funded natural products research.

Since 1986, NPB has received tens of thousands of samples from the branch’s contractors, which for plants includes the University of Illinois at Chicago, the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Ill., World Botanical Associates in Calif., and the New York Botanical Gardens. For marine collections, the Coral Reef Research Foundation in Palau and the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences are the two major contractors.

Specimens collected from these teams are almost immediately shipped – frozen if marine and air-dried if plants – to NPB’s repository, and stored in a freezer set at -18 degrees Celsius (about zero degrees Fahrenheit), where they stay until ready for extraction – the process that involves grinding down a sample with everything from hammer mills to meat grinders, and mixing it with water or an organic solvent.

The NPB’s Extraction Laboratory, headed up by Thomas McCloud of SAIC-Frederick, Inc., is responsible for getting whole specimens down to that pile of dust, into those solutions, and ready for research.

“We are building a library of extracts,” McCloud says. We’ve had over 200,000 extraction samples available in the repository just over the last 20 years for cancer, AIDS, and other disease-oriented research, McCloud adds.

After the samples are whittled down, they are placed into one of the facility’s 10, two-story freezers, which are tucked away in a warehouse, along with the extraction lab, at the NCI-Frederick campus on the Fort Detrick military base. And with an open door policy, any National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institute or external research center can request these specimens, with a Material Transfer Agreement, which protects the rights of the countries of origin. That agreement, based on the NCI Letter of Collection, was in place three years prior to the Convention on Biological Diversity agreement that was signed by over 150 nations at the United Nations Earth Summit in 1992.

With less than 10 percent of the world’s plant and marine species investigated, and thousands of specimens at NPB still waiting to be tested, it’s safe to say that researchers have their work cut out for them. But with samples coming in and out almost every day, Dr. Newman reports, the chances of finding the next great discovery from nature are only getting better.