Meetings and Events

Spring 2013

Vol. 8, Issue 1

Winter 2013

Vol. 7, Issue 2

Spring 2012

Vol. 7, Issue 1

Spring 2011

Vol. 6, Issue 1

Fall 2011

Vol. 6, Issue 2

Spring 2010

Vol. 5, Issue 1

Fall 2010

Vol. 5, Issue 2

Spring 2009

Vol. 4, Issue 1

Fall 2009

Vol. 4, Issue 2

Spring 2008

Vol. 3, Issue 1

Fall 2008

Vol. 3, Issue 2

Fall 2007

Vol. 2, Issue 2

Winter 2007

Vol. 2, Issue 1

Summer 2006

Vol. 1, Issue 2

NCI grantee explores Vitamin C as potential cancer therapy

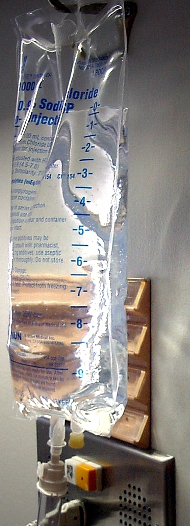

Although it is usually associated with oranges and possibly preventing colds, vitamin C may also be a potential cancer therapy. The history of vitamin C (also known as ascorbate) and cancer spans a few decades, going back at least to the 1970s. Early experiments using high doses of vitamin C supplements and intravenously administered vitamin C suggested that vitamin C may help treat cancer.Two randomized, controlled clinical trials using only vitamin C supplements found no beneficial effects on cancer and scientists lost interest in researching this vitamin as a cancer therapy. However, this issue was revisited in the mid-1990s when studies suggested that orally and intravenously administered vitamin C are not processed the same way in the body. Researchers discovered that when vitamin C is administered intravenously at high doses, resulting concentrations in the blood are much higher compared to vitamin C that is taken orally. Subsequently, a number of studies have been published indicating that high-dose (pharmacological) vitamin C may in fact help kill cancer cells and research is continuing in this area. Dr. Joseph Cullen of the University of Iowa has recently been awarded a U01* from the National Cancer Institute to investigate pharmacological ascorbate used along with radiation in pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Cullen’s U01 grant is a follow-up to an earlier R21 grant** he received to examine mechanisms of ascorbate-induced death of pancreatic cancer cells. “I initially became interested in ascorbate after hearing Mark Levine (who is currently at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health) present his work, which was done in collaboration with my colleague Garry Buettner at the University of Iowa. At the time, I was doing research on other oxidizing compounds in pancreatic cancer and it made sense to pursue work with ascorbate.” Dr. Cullen’s results suggested that ascorbate kills pancreatic cancer cells by increasing levels of hydrogen peroxide, which is very toxic to cells. Animal studies were also conducted. In those experiments, mice were implanted with pancreatic cancer cells and then received injections of ascorbate or saline for 2 weeks. Dr. Cullen noted that the animal studies revealed “striking results with virtually no side effects.” In the animals that received ascorbate treatment, tumors grew more slowly than in animals that received saline injections. On day 21 of the experiment, the tumors in saline-treated animals were three times larger than in ascorbate-treated animals. In addition, the animals that received ascorbate lived longer than animals that received saline injections.

The goal of the new grant is to determine if pharmacological ascorbate can improve the effects of radiation therapy in pancreatic cancer. Dr. Cullen plans to test this by conducting experiments in pancreatic cancer cells and in animals. For the in vitro experiments, Dr. Cullen will determine if ascorbate makes pancreatic cancer cells more susceptible (compared to healthy cells) to radiation. He will also investigate the mechanisms behind the increased sensitivity. One way that radiation therapy is effective is by increasing levels of reactive oxygen species (such as hydrogen peroxide), which damage cells. Dr. Cullen hypothesizes that combining ascorbate with radiation will make cancer cells more vulnerable to the treatment due to increased levels of hydrogen peroxide. If the in vitro experiments are successful, they will be followed by work in animals. Those experiments, which will investigate if ascorbate can increase sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to radiation without damaging healthy cells nearby, will be critical to future clinical trials. For example, Dr. Cullen is interested in conducting a clinical trial combining ascorbate with radiation and chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer patients.

Dr. Cullen has recently published*** results of a phase I trial looking at the safety of using pharmacological ascorbate in addition to standard gemcitabine chemotherapy treatment in pancreatic cancer patients. He found that there were no serious side effects associated with the ascorbate treatment, indicating that it may be safe to use as a complementary cancer therapy. Dr. Cullen commented, “The results of this trial were surprising. Most patients with this type of cancer survive for only 6 months, but the mean survival time of patients in our study was 13 months. We even had one patient live more than 2 years.” However, since the study did not include randomization with a group that received gemcitabine alone, these results cannot be used to confirm a benefit of the ascorbate.

Dr. Cullen is planning on extending this work to other cancer types. Clinical trials are underway investigating the effects of combining ascorbate with standard treatment in patients with glioblastoma and lung cancer.

Dan Xi, Ph.D., Program Director at the Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine noted, “There is a critical need to improve the efficacy of current therapy for pancreatic cancer. Using pharmacological ascorbate to enhance pancreatic cancer cell sensitivity to death by radiation therapy is innovative and the research team led by Dr. Cullen has extensive experience in this field. If successful, the result could lead to the potential initiation of a clinical trial.”

*Project number: 1U01CA166800-01A1

**Project number: 5R21CA137230-02

*** Welsh, J.L., Wagner, B.A., van't Erve, T.J., Zehr, P.S., Berg, D.J., Halfdanarson, T.R.,…, & Cullen, J.J. (2013). Pharmacological ascorbate with gemcitabine for the control of metastatic and node-positive pancreatic cancer (PACMAN): results from a phase I clinical trial. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology, 71 (3), 765-75.